The ancient Silk Road was a vast network of trade routes whose flow of ideas, culture, music, and art crossed the mountains and deserts of Central Asia to connect East Asia and the Mediterranean. At the heart of the Silk Road was the exchange of ideas, goods, and technologies. The people who were part of these exchanges met and saw each other's fashions, ate each other's food, heard each other's music.

Similarity between dance and Music of central Asia and north India:

The historic Persian Empire encompassed a great majority of Central Asia, from the shores of the Mediterranean in the west, through Transoxiana in the north to the borders of China in the east. Persian culture had a profound and lasting influence on the literature and art of the societies that traded along the Silk Road. Iran is the name of the country that is at the geographic center of this once vast empire, and the Persian cultural influence extends well beyond the borders of present day Iran.

A certain Persian elegance came into Indian performing arts, literature; architecture etc. Ref. of ‘Babarnama’ dancers imported from Central Asia spread their ideas to Kathak dancers, as they borrowed ideas from Kathak to implement in their own dance. Kathak absorbed the new input, adapting it until it became an integral part of its own vocabulary.

As per the similarity of 12 Maqam System with Indian Raga’s (according to the Indian Manuscripts), Persian dance from central Asia and Kathak classical dance from North India,have many similarities. There are many overlapping 'Mudras' (hands gestures) in Kathak which can be seen in the 'harikat' (Central Asian word for gesture) from the neighbouring regional dance styles of East Turkestan (Uyghur style dance), Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan and Iran.

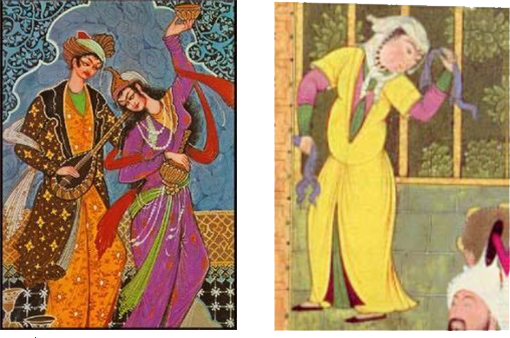

Iranian Persian female dancers and musicians performing in court, a historical painting from Hasht Behesht palace, Isfahan, Iran, from 1669

The arrival of scholars and artists in India from central Asia

The arrival of scholars, artisans and performing artistes from major centres of Islamic culture owing to the devastations caused by Chingiz Khan in A. D. 1220-21 led to the further strengthening of Persian traditions in India to which early Sultans firmly clung. However, this aloofness could not be maintained for long, and a slow process of assimilation to indigenous culture and performance practices started during the half of the thirteenth century.

This brought a change in the cultural set-up of northern India, in the beginning of the thirteenth century. As the new elite had come from a culturally developed region and their traditions were in many ways different from those current in northern India, major change appeared in the patronage pattern. There was a sharp decline in the status of ganikas, who occupied a coveted place in Indian cultural tradition. The new patrons, who conformed to Turko-Persian traditions of art and culture, had no knowledge and understanding of the Sanskrit language and lacked interest in the arts which were the attributes of a ganika. As a result she lost her pride of place in society.

While in the pre-Sultanate days Sangit was the amalgam of acting, dancing and singing, and the knowledge of the stagecraft was considered an essential accomplishment for the fashionable people of society, in the new scheme of entertainment theatre had no place. The elimination of theatre from the majlisi hunar (accomplishments appropriate to convivial assemblies) led to a tremendous decline in the status of the theatre artistes. A further change was brought about in the connotation of the term sangit during the period under review; it now included the three arts of vocal music, instrumental music and dance.

1st *Persian painting showing a dancer and a musician.

2nd * A picture of a lady dancing with two smalls carves from “Siyavash and Fanagis Wedded” folio 185, Metropolitan Museum of Arts

The transition:

The transition from Turko-Persian musical traditions began more markedly during the reign of Sultan Muizzuddin Kaqubad (r. 1287-1290). In him the performing artistes, who were sitting idle at his grandfather Sultan Ghiyasuddin Balban (r. 1267-87), found an agreeable patron.

According to Ziauddin Barani, the author of Tarikh-i Firuzshahi, there grew a colony of musicians, pretty-faced entertainers, jesters and bhands from every region in the vicinity of the palace Kilukhari where the Sultan held public audience. He further writes that Indian performing artistes, courtesans, slave girls, and slaves were trained in the Persian language and instructed in the manners and customs of the court. They were also trained in Persian music (sarud), and playing of chang, rubab, kamancha, maskak, nay, and tambur, the instruments used in the Persian cultural sphere. Experts in Persian and Indian music composed eulogies of Sultan in the form of qaul and ghazal which they rendered in every musical air.

Barani’s observations are extremely significant. In fact, they reflect the efforts of Indian performing artistes to adapt to the changing demands of the period and match the taste of the new patrons. They mastered the Persian language which had emerged as the language of the new aristocratic circle; they became expert in the latest styles and techniques of musical arts popularized by the central Asian and Khurasani musicians. Thus, there was a temporary setback to the community of natas, the traditional instructors of Sangit. By adapting themselves to the new artistic requirements they retained their status as instructors of musical arts until the end of the seventeenth century.

A process of the assimilation of Indian and Persian musical tradition also started about this time. Many of the early medieval musical forms such as suryaprakash and chandrapakash began to be performed by Muslim musicians. These forms have been mentioned in the Persian musical treatises as marg music, and their knowledge was considered essential for the nayaks (maestro) even as late as the nineteenth century. Geet had a profound influence on many of the musical forms which took place during the thirteenth century, especially qaul which had a striking similarity with it to the extent that it was regarded as the equivalent of geet. Some of the instruments, especially nay or shahnai became associated with Indian rituals and festivities.

Contribution of the Chishtiya Order to Devotional Music in India

The Bhakti cult is the counter part of Islamic mysticism and Sufism, which taught us humanism and Sufism. The Bhakti movement originated in south India and spread northwards between the 12th and 18th centuries by Ramanuja. By the end of 14th Century, it also covered the whole of North India in a big way, and resulted in the mingling of Hindu mysticism with Sufism. The Sufi movement therefore was the result of the Hindu influence on Islam. This movement influenced both the Muslims and Hindus and thus, provided a common platform for the two.

The Sufis believed in the concept of Wahdat-ul- Wajud (Unity of Being). The great Sufis of India were invariably men of deep learning and used to write in Persian as well as in Indian languages. Chishtiya order of Sufi that was established in Ajmer, Rajasthan, by Moinuddin Chishti (d.1233), the greater Sufi of India. He was succeeded by Khawaja Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki. Hazarat Nizammuddin Auliya was the successor of Hazrat Ganj I Shakar. While mentioning this great Saint of Delhi, one has to remember his favourite disciple Hazarat Amir Khusrow, who had a strong links with the Sufi khanqah of the Chishti order which was the most effective venue of cultural sharing. He was a devotee and well versed in the practices related to sama (Sufi music).

The roots of Qawwali can be traced back to 8th century Persia (Iran). During the first major migration from Persia, in the 11th century, the musical tradition of Sama migrated to the Indian Sub-Continent, Turkey and Uzbekistan. In the late 13th century, Hazrat Amir Khusro Dehelvi of the Chishty order of Sufis is credited with fusing the Persian and Indian musical traditions to create Qawwali. The word Sama is often still used in Central Asia and Turkey to refer to forms very similar to Qawwali, and in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, the formal name used for a session of Qawwali is Mehfil-e-Sama. Qaul (Arabic: قَوْل) is an "utterance {of the prophet (SAW)}", Qawwal is someone who often repeats (sings) a Qaul, Qawwali is what a Qawwal sings. They employed handclaps for making the rhythm. Even the most exalted and proud vocalists were taken aback by their art.

Sufi dancing during sama’s gathering, source: Walter art museum, Baltimore

In the realm of Sufiana music, Amir Khusrow’s qalaams continue to be recited by the qawwals in the ‘sama’ mehfils of the dargahs of Sufis.Amir Khusrau, contributed tremendously to the development of their music by synergizing Indian and Central Asian styles, by ‘inventing’ several new ragas (modes), genres (such as the Khayal, Qawwali and Tarana), instruments (such as the sitar and tabla), and by composing many songs. Interesting anecdotes illustrating his musical genius and ‘inventions’ are circulated, some of them rather improbable. The mystics such as those of the Chishti order permeated the rural fabric of India, preaching the message of Islam in local dialects and cultural forms.

Court Culture

It was in fact a unique phenomenon of the fourteenth century that court culture came in close contact with folk culture through persons who were intimate with both the circles; Thus Khusrau had the rare opportunity of acquiring knowledge of Turko-Persian court traditions, as well as Indian classical and folk traditions, which were taking roots in sama. He combined this knowledge in the fashioning of Qaul, Tarana, Tillana, Naqsh, Nigar, Basit, Fard, Farsi and Sohla. In these musical forms Khusrau blended Indian and Persian music techniques. For mass appeal he composed songs in desi, the spoken dialect of the Delhi region.

During this period the traditional prabandh form was denounced by Indian poet saints and adopted chhand, pad and doha. They also began to compose in regional languages. It is in this scenario that most of the musical forms, such asshabd, dhrupad, and bishnupad took shape in due course. A good part of medieval music, thus, evolved in a religious setting, but one which assimilated strands from both popular Hindu and popular Islamic forms.

The traditions which evolved with the Khaljis continued to flourish during the fourteenth century under the Tughlaqs. Glimpses of these are preserved in the accounts of The Arab travelers Ibn-i Battuta and Shahabuddin al-Umari, who came to India during the reign of Muhammad bin Tughlaq (r. 1325-51). The musicians of Delhi lived in a separate colony called Tarababad which was located near Hauz- i Khas. Their colony (Ibn-i Battuta calls it “market”) was one of the largest in the world. A similar locality/market existed at Daultabad, the new capital founded by Muhammad bin Tughlaq in the Deccan. Interestingly, both these places had mosques which were frequented by women musicians in large numbers.

We can see that a number of profound changes took place both in music and dance during the period under review. Some of the people musical forms went out of vogue. The popularity of dhrupad, too decrease considerably. Dua to a marked decline in court patronage, eminent musicians were obliged to seek employment outside Court Circus and this disproved a blessing in disguise. There insued a popularization of those techniques hitherto reserved for a selected few, also music begin to drive on the support of the folk traditions which were as vibrant as the classical ones.

The blending of the classical and folk music patterns of the Delhi region resulted in the reinvigoration of Khayal and Tappa which become exceedingly popular during the 18th century; the musical patterns formed by the Qawwals were integrated into a composite form called Qawwali Marsiya-Khawani also developed as a distinct genre. During the 19th Century, Thumri and Dadra were strengthened by the classical traditions. The dance art also achieved great prominence, especially under the patronage of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, the refined and folk style of dance and dance drama were synthesized in the form of Kathak. The age was, thus, one of the experimentation vividness appears to be the key-note of the artist dynamism. The patrons too were enthusiastic; they provided support and encouragement for experiments and developments of fashioning and strengthening new forms of music and dance style which are popular event to this day.